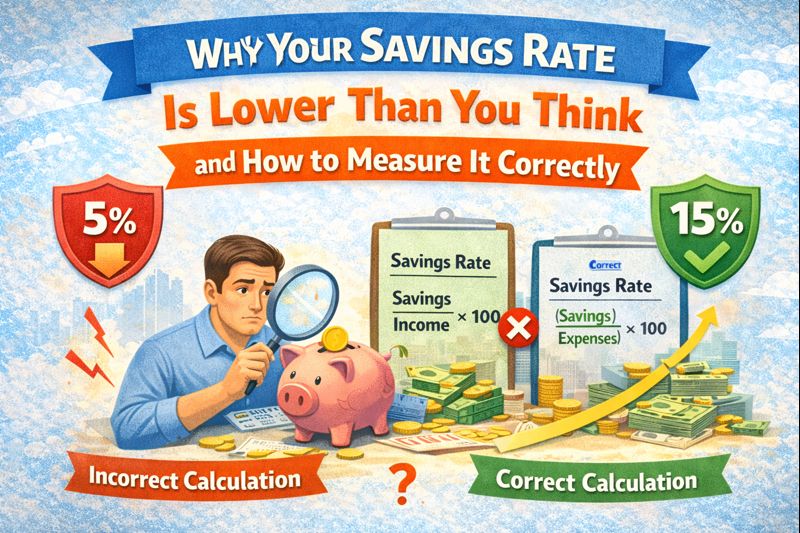

Why Your Savings Rate Is Lower Than You Think and How to Measure It Correctly?

If someone asked you right now what your savings rate is, could you give them an accurate answer? Most people can’t. They might say something like “around 15%” or “pretty good, I think,” but when you dig into the actual numbers, the reality is often sobering. I’ve seen countless people confidently claim they’re saving 20% of their income, only to discover through careful calculation that their true savings rate is closer to 8% or 10%. This isn’t because they’re lying or delusional it’s because measuring your savings rate correctly is surprisingly tricky, and most people are making one or more critical calculation errors that inflate their perceived savings.

This matters enormously because if you think you’re saving 18% when you’re actually saving 11%, you’re not just slightly off track you could be seven years behind on your retirement goals without realizing it. You’re making financial decisions based on false information, and that can have devastating long-term consequences. The good news is that once you understand the common measurement mistakes and learn to calculate your savings rate correctly, you gain crystal-clear insight into your actual financial trajectory. You might discover you’re doing worse than you thought, which is uncomfortable but actionable. Or you might find you’re doing better than you realized, which is encouraging and motivating. Either way, accuracy is the foundation of effective financial planning.

Mistake 1: Confusing Gross Income With Take-Home Pay

The most fundamental error in calculating savings rate is inconsistency between the numerator and denominator. Your savings rate is a percentage, which means you’re dividing what you save by what you earn. But here’s where people get confused: some calculate based on gross income (before taxes), others use net income (after taxes), and many switch back and forth without realizing it, creating completely meaningless numbers.

Let’s say you earn $80,000 annually before taxes, take home $58,000 after taxes, and save $12,000. If you calculate based on gross income, your savings rate is 15%. If you calculate based on net income, it’s 20.7%. That’s a massive difference—more than five percentage points—for the exact same savings behavior. Neither calculation is wrong per se, but inconsistency is wrong, and most people don’t even realize they’re being inconsistent.

The bigger problem comes when people count some savings against gross income and other savings against net income without realizing it. They think, “I save $500 monthly to my savings account, which is about 10% of my take-home pay, plus I contribute 6% to my 401(k) pre-tax, so I’m saving about 16% total.” But that math doesn’t work—you’ve mixed denominators. The 401(k) contribution is 6% of gross income, while the savings account is measured against net income. You can’t just add those percentages together.

Choosing Your Denominator Consistently

The solution is picking one denominator and sticking with it religiously. I recommend using gross income for most people because it’s more conservative (gives you a lower, more challenging savings rate), it’s easier to track (gross income doesn’t fluctuate with tax withholding changes), and it makes comparisons to savings rate benchmarks more accurate since most financial advice uses gross income.

Here’s how to do it correctly: Take your annual gross income from your W-2 or tax return. Then add up everything you saved that year—401(k) contributions, IRA contributions, savings account deposits, investment account contributions, even your employer match. Divide total savings by gross income and multiply by 100. That’s your real savings rate.

On that $80,000 gross income example, let’s say your savings breakdown is: $4,800 to 401(k) (6%), $2,400 employer match (3%), $3,600 to IRA ($300 monthly), and $1,200 to emergency fund ($100 monthly). Total savings: $12,000. True savings rate: 15%, not the 16% or 20% that incorrect calculations might have suggested.

Mistake 2: Not Including Employer Contributions in Your Savings

This is one of the most common ways people underestimate their savings rate, and it creates real problems for financial planning. Many people calculate their savings rate based only on their own contributions, completely ignoring employer 401(k) matching or other employer retirement contributions. This makes them think they’re saving less than they actually are, which sounds harmless but can lead to poor decisions.

If you’re contributing 5% to your 401(k) and getting a 3% employer match, your actual retirement savings rate is 8%, not 5%. That employer match is real money that increases your net worth just as much as your own contributions. It should absolutely count toward your savings rate calculation. Excluding it gives you an artificially deflated view of your savings progress.

Why does this matter? Because if your target is a 15% savings rate and you think you’re only at 5% (not counting the 3% match), you might panic and make overly aggressive cuts to your lifestyle. In reality, you’re at 8% and just need to find another 7 percentage points, not 10. Accurate measurement leads to appropriate action.

The same principle applies to any employer retirement contribution—pension contributions, profit-sharing deposits, or stock grants that vest and you hold rather than sell. If your employer contributes money that builds your wealth, it counts as savings even though it didn’t come directly from your paycheck.

The Full Picture of Retirement Contributions

Calculate your complete retirement savings rate this way: Add your 401(k) deferrals, employer matching contributions, any profit-sharing contributions, IRA contributions (Roth or traditional), HSA contributions (which many people forget), and any other tax-advantaged retirement savings. Divide by your gross income.

For example, on $90,000 gross income: 401(k) contribution $7,200 (8%), employer match $3,600 (4%), IRA contribution $6,500, HSA contribution $3,850. Total retirement savings: $21,150, which is a 23.5% retirement savings rate—dramatically different than the 8% you might have thought if you only counted your 401(k) contribution.

Mistake 3: Forgetting About Irregular Contributions and Windfalls

Most people calculate their savings rate based on regular monthly contributions—the $500 that automatically goes to savings, the 6% to the 401(k), maybe the $200 to an investment account. But they completely forget about irregular contributions and windfalls that actually represent significant savings throughout the year.

Did you get a tax refund and deposit it into savings? That’s savings. Did you get a year-end bonus and invest half of it? That’s savings. Did you sell something valuable and bank the proceeds? Savings. Did you make extra principal payments on your mortgage beyond your regular payment? Many would count that as savings too. These irregular contributions can easily add up to thousands of dollars annually, but because they’re not part of your monthly routine, people often forget to include them when calculating their savings rate.

I’ve seen people claim they save “about 12%” when their regular monthly contributions do work out to roughly 12% of their income. But then you discover they got a $6,000 tax refund that went to savings, a $4,000 bonus that went to investments, and they made $2,400 in extra mortgage principal payments throughout the year. On a $75,000 income, that’s an additional $12,400 in savings beyond the regular monthly contributions—increasing their true savings rate from 12% to 28.5%.

The Annual Reconciliation

The only way to get this right is to calculate your savings rate annually rather than monthly, or at minimum to do an annual reconciliation that captures all contributions including irregular ones. At the end of each year, go through your accounts:

List every deposit to savings accounts, every contribution to investment accounts, every retirement account contribution, every extra debt payment you’re counting as savings. Add it all up. That’s your numerator. Your denominator is your total gross income for the year including salary, bonuses, side income, and any other earnings. This annual calculation captures the complete picture including all those irregular contributions you’d miss in a monthly calculation.

For most people, this annual reconciliation reveals they’re saving more than they thought, which is encouraging. But occasionally it reveals the opposite—maybe you thought you were saving $500 monthly all year but actually missed a few months, or you pulled money out of savings for something you forgot about. Either way, you need accurate data to make good decisions.

Mistake 4: Counting Money That Isn’t Really Savings

On the flip side, some people inflate their savings rate by counting things that aren’t actually savings. This creates a false sense of security that’s potentially more dangerous than underestimating your savings rate because it makes you think you’re on track when you’re not.

The most common error is counting minimum debt payments as savings. If you have a $300 monthly student loan payment or a $450 car payment, that’s not savings—it’s an obligation. You borrowed money, you’re paying it back, and yes, paying down principal does increase your net worth, but it’s fundamentally different from saving.

Some people argue that extra principal payments beyond the minimum should count as savings, and there’s a reasonable case for that since you’re voluntarily increasing your net worth. I’m somewhat sympathetic to this view, but it’s important to distinguish between retirement savings (which will fund your future living expenses) and debt paydown (which reduces future obligations but doesn’t create income). They’re not equivalent even if both increase net worth.

Another common inflation error is counting money you intend to spend soon as “savings.” If you’re setting aside $200 monthly for Christmas gifts, that’s budgeting, not saving. When December comes, that money gets spent—it never actually accumulated. Same with vacation funds, car replacement funds, or home repair funds. These are important to set aside, but they’re deferred spending, not savings that will compound and fund your financial independence.

True Savings Definition

For your savings rate to be meaningful, count only money that meets these criteria: it increases your net worth, you don’t plan to spend it within the next year, and it will contribute to funding your future financial independence. This includes retirement accounts, investment accounts you’re building for the long term, HSAs (if you’re using them as retirement vehicles), and potentially extra principal payments on mortgages or low-interest debt.

It does not include: minimum debt payments, money saved for near-term planned expenses, checking account buffers that just sit there, or money you’re likely to spend within 12 months. Getting this distinction right is crucial for understanding whether you’re actually building wealth or just managing cash flow effectively (both are important, but they’re different).

Mistake 5: Not Accounting for Account Value Changes

Here’s a subtle but important error: some people calculate savings rate based on account balances rather than contributions. They see their investment account grew from $50,000 to $58,000 over the year and think they saved $8,000. But if they only contributed $4,000 and the other $4,000 was investment returns, their savings rate should be based on the $4,000 contribution, not the $8,000 growth.

This matters because your savings rate measures your savings behavior—what you’re controlling—while investment returns measure market performance, which you don’t control. Mixing the two obscures whether you’re actually saving enough. In good market years, this error makes your savings rate look artificially high. In bad market years when your accounts might decrease in value despite contributions, it makes your savings rate look artificially low or even negative.

The correct approach is to track contributions only. Add up every dollar you deposited into savings and investment accounts during the year. Ignore changes in account values due to investment returns or losses. Your savings rate is about the flow of money from income to savings, not about portfolio performance.

This gets slightly tricky with automatic dividend reinvestment. If dividends are automatically reinvested, technically that’s not new savings—it’s investment returns being deployed. However, many people reasonably count dividend reinvestment as part of their savings since they’re making the choice not to spend those dividends. The key is being consistent about how you handle this.

Separating Savings Rate From Investment Returns

Track two separate metrics: your savings rate (contributions divided by income) and your investment return rate (portfolio growth divided by starting portfolio value). These two numbers together tell you how your wealth is growing. Your savings rate is what you control; your investment return is what the market does. Keeping them separate gives you clarity about which factors are driving your wealth accumulation.

For example, you might have a 20% savings rate and an 8% investment return in a given year. The 20% tells you about your behavior and discipline; the 8% tells you about market performance. Next year if you have a 22% savings rate and a -5% investment return, you’ve actually improved your financial behavior even though your account balances might not show it.

Mistake 6: Overlooking Tax-Advantaged Accounts and Their True Value

Many people underestimate their savings rate because they don’t properly account for the tax advantages of certain savings vehicles. A dollar contributed to a traditional 401(k) isn’t the same as a dollar contributed to a taxable savings account—the 401(k) dollar costs you less in actual take-home pay due to the tax deduction, but it’s still a full dollar of savings.

Here’s what this looks like: You contribute $10,000 to a traditional 401(k). If you’re in the 22% tax bracket, that contribution only reduces your take-home pay by $7,800 because you save $2,200 in taxes. Some people think their savings rate should be based on the $7,800 cost rather than the $10,000 saved. But that’s incorrect—you saved $10,000, full stop. The fact that it cost you less to save it is a bonus, not a reason to discount the savings.

This matters significantly when calculating your true savings rate. If you’re maximizing your 401(k) at $23,000 annually (2024 limit for people under 50) and earning $100,000, that’s a 23% savings rate from that source alone. The fact that it only cost you $17,940 in reduced take-home pay (in the 22% bracket) is wonderful, but your savings rate is still 23%, not 17.94%.

The Roth vs Traditional Confusion

This gets more confusing with Roth accounts. With a Roth IRA or Roth 401(k), you’re contributing after-tax dollars, so there’s no tax deduction. If you contribute $6,500 to a Roth IRA, it costs you the full $6,500 in take-home pay. But the savings amount is still $6,500, counted the same way you’d count a traditional IRA contribution.

Some people mistakenly think Roth contributions should be weighted more heavily in savings rate calculations since they “cost more” due to the lack of tax deduction. This is backwards thinking. Your savings rate measures how much you’re setting aside, not the tax treatment. A $6,500 Roth IRA contribution and a $6,500 traditional IRA contribution both represent the same savings rate—they’re just treated differently for taxes, which is a separate consideration.

The key principle: Count the full amount saved regardless of the tax treatment. Your savings rate is about setting money aside for the future, and whether that money went in pre-tax or post-tax doesn’t change the fact that you saved it.

Mistake 7: Ignoring the Impact of Debt Payments on Net Savings

Here’s a more philosophical but crucial question: if you’re contributing to your 401(k) while simultaneously accumulating credit card debt, is your savings rate what it appears to be? Technically yes—you are saving money. Practically, your net wealth accumulation is being eroded by growing debt, which means your effective savings rate is lower than the nominal rate.

This is where the distinction between gross savings rate and net savings rate becomes important. Your gross savings rate is what you’re contributing to savings and investment accounts. Your net savings rate accounts for changes in debt. If you saved $10,000 but accumulated $4,000 in credit card debt during the same period, you could argue your net savings rate should be based on $6,000 net wealth increase rather than $10,000 gross savings.

Most financial advisors recommend tracking gross savings rate because it measures your savings behavior separately from your debt situation, which should be addressed independently. But you should also be aware of your net wealth change. If you have a 20% savings rate but your net worth isn’t growing at 20% of your income because debt is increasing, that’s a red flag requiring attention.

The practical impact: Don’t let a strong savings rate blind you to problematic debt accumulation. Someone who saves 15% while adding 10% to their debt load annually isn’t in nearly as good shape as someone who saves 15% while adding no debt. Both have 15% savings rates, but their net financial trajectories are dramatically different.

The Net Worth Growth Reality Check

Once a year, calculate your net worth change as a percentage of income. Take your net worth today minus your net worth one year ago, and divide by your annual income. This gives you a “net savings rate” that accounts for debt changes, investment returns, and everything else. Compare this to your calculated savings rate.

If your savings rate is 18% but your net worth only grew by 9% of your income, something’s wrong—either debt increased, investment returns were terrible, or you had major expenses that depleted savings. If your net worth grew by 26% of your income despite an 18% savings rate, you enjoyed strong investment returns or paid down debt, which is great. This reality check keeps your savings rate calculation honest.

How to Calculate Your Savings Rate Correctly: The Complete Method

Let’s put all of this together into a step-by-step method for calculating your true savings rate accurately. Do this calculation annually to get the most accurate picture.

Step 1: Calculate Total Gross Income Add up all W-2 income, 1099 income, bonus income, side hustle earnings, and any other income you received during the year. This is your denominator. Do not subtract taxes—use the gross amount.

Step 2: List All Retirement Contributions

- Your 401(k), 403(b), or similar contributions (find this on your final pay stub or W-2)

- All employer matching or profit-sharing contributions (also on your pay stub or annual benefits statement)

- Traditional IRA contributions

- Roth IRA contributions

- SEP-IRA or Solo 401(k) if self-employed

- HSA contributions (yes, these count as savings)

- Any other retirement account contributions

Step 3: List All Non-Retirement Savings

- All deposits to savings accounts throughout the year

- All deposits to taxable investment/brokerage accounts

- Any extra principal payments on mortgages (if you count these)

- Any other wealth-building contributions

Step 4: Add Up Total Savings Sum everything from Steps 2 and 3. This is your numerator.

Step 5: Calculate the Percentage Divide total savings by total gross income and multiply by 100.

Example Calculation:

- Gross income: $95,000 (W-2: $90,000, side income: $5,000)

- 401(k) contribution: $9,500 (10% of W-2)

- Employer match: $4,500 (5% of W-2)

- Roth IRA: $6,500

- HSA: $3,850

- Savings account deposits: $2,400

- Investment account deposits: $3,000

Total savings: $29,750 Savings rate: $29,750 ÷ $95,000 = 31.3%

This person might have thought they were saving “about 10%” if they only looked at their 401(k) contribution. The reality is dramatically better—31.3%—once you properly account for all savings including employer contributions, IRAs, HSA, and regular savings deposits.

What to Do Once You Know Your Real Number

Once you’ve calculated your actual savings rate correctly, you have three possible outcomes:

Outcome 1: You’re Saving More Than You Thought This is encouraging but shouldn’t lead to complacency. Confirm that your rate is sufficient for your goals using retirement calculators. If you’re truly on track, great—maintain the discipline. Consider whether you could sustainably increase further to reach goals sooner or build additional financial security.

Outcome 2: You’re Saving Less Than You Thought This is uncomfortable but valuable information. You now know the gap between where you are and where you need to be. Calculate what savings rate you actually need to reach your goals, then create a concrete plan to increase from your current real rate to your target rate. Break this into annual milestones—if you’re at 9% and need to reach 20%, plan to hit 12% this year, 15% next year, and so on.

Outcome 3: You’re Close to What You Thought Lucky you—your estimation was accurate. But now you have precision instead of approximation, which allows for better planning. Use your accurate baseline to set specific improvement targets and track progress reliably.

Regardless of outcome, recalculate your savings rate annually using this consistent methodology. Track it over time to ensure you’re making progress. This accurate tracking transforms your savings rate from a vague notion into a concrete metric you can manage and improve systematically.

The truth about your savings rate—whatever it is—is infinitely more valuable than a comforting illusion. You can’t fix problems you don’t accurately measure, and you can’t maintain discipline without clear feedback on whether your efforts are working. Calculate your savings rate correctly, face the number honestly, and use it as the foundation for financial decisions that actually serve your long-term goals. Your future self will thank you for the clarity.