Common Savings Rate Mistakes That Keep People Stuck Living Paycheck to Paycheck

There’s a special kind of frustration that comes from feeling like you’re doing everything right financially, yet somehow you’re still living paycheck to paycheck. You have a decent job, you’re not recklessly spending money, and you’re genuinely trying to save but the emergency fund never seems to grow, retirement feels impossibly distant, and one unexpected expense can still derail your entire month. If this sounds familiar, the problem probably isn’t your income or even your spending. The problem is likely one or more fundamental mistakes in how you’re approaching your savings rate.

These aren’t the obvious mistakes like “stop buying lattes” that personal finance gurus love to drone on about. These are deeper, more structural errors that keep smart, hardworking people trapped in a cycle of financial stress despite their best intentions. The insidious part is that many of these mistakes feel like responsible financial behavior on the surface. You think you’re making good decisions, but the underlying approach is flawed in ways that guarantee you’ll stay stuck. Let’s break down the most common savings rate mistakes that keep people living paycheck to paycheck, and more importantly, how to fix them starting today.

Mistake 1: Saving Whatever’s Left Over Instead of Paying Yourself First

This is the granddaddy of all savings mistakes, and it’s so common that most people don’t even recognize it as an error. The thinking goes like this: “I’ll pay all my bills, cover my expenses, and whatever’s left at the end of the month, I’ll save.” It sounds reasonable. It feels responsible. And it guarantees you’ll never build wealth.

Here’s why this approach fails: there’s never anything left over. Expenses expand to fill available income. This isn’t a character flaw—it’s human nature. When you know you have $3,500 in your checking account after bills are paid, you unconsciously give yourself permission to spend closer to that full amount. An extra dinner out here, a small upgrade there, a “treat yourself” purchase because you’ve been working hard. By the end of the month, your checking account has $200 left, and you tell yourself you’ll save more next month when things aren’t so tight.

But next month is never different. There’s always something—a birthday gift to buy, a needed household item, a minor car repair. The “save what’s left” approach treats savings as optional, as a luxury you’ll get to once everything else is handled. And since there’s always something else that needs handling, savings never happens.

The fix is simple but requires a mental shift: pay yourself first. Your savings isn’t what’s left after expenses—it’s the first expense, non-negotiable and automatic. If your target is 20% savings rate, that money leaves your account before you pay rent, before you buy groceries, before you do anything else. You don’t see it, you don’t touch it, and you certainly don’t consider it available for spending.

This forces you to live on the remaining 80%, which is completely manageable because you never had access to that other 20% in the first place. It’s the difference between willpower-based saving (which fails) and system-based saving (which succeeds). Set up automatic transfers to savings and investment accounts for the day after your paycheck hits. Remove the decision entirely, and suddenly saving becomes effortless rather than impossible.

Mistake 2: Not Counting the Employer Match in Your Savings Rate

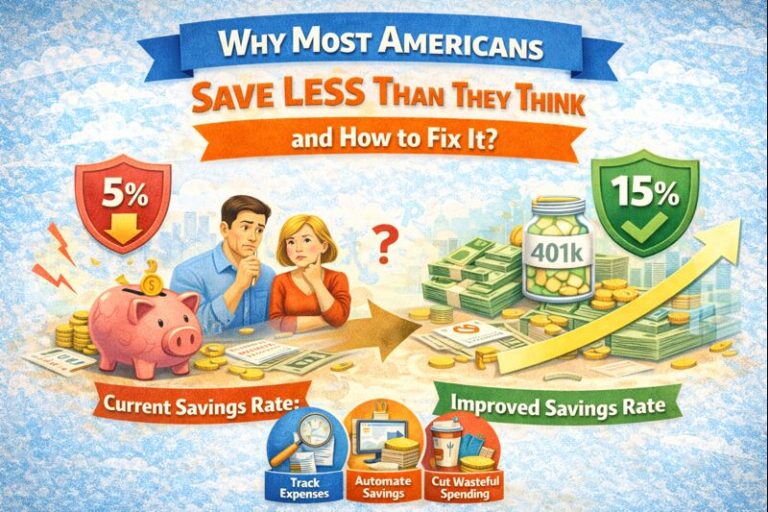

This mistake is particularly common among people who are technically saving but don’t realize how much they’re actually saving. Let’s say you contribute 6% of your salary to your 401(k), and your employer matches 3%. If someone asks about your savings rate, you might say “six percent,” but your actual savings rate is nine percent—you’re just not taking credit for the free money your employer is contributing.

Why does this matter? Because not counting the employer match causes you to underestimate your progress and potentially under-save in other areas. If you think you’re only saving 6% when you’re actually saving 9%, you might not realize you’re closer to your savings goals than you believe. Conversely, if you’re only contributing 3% personally and not getting the full employer match, you’re leaving free money on the table—potentially thousands of dollars annually.

The employer match is real money that increases your net worth. It should absolutely count toward your savings rate calculation. If your goal is a 15% savings rate and you’re getting a 4% employer match, you only need to contribute 11% personally to hit that target. Understanding this correctly can make your savings goals feel more achievable and help you make better decisions about where to allocate additional savings.

Here’s the action step: calculate your total savings rate including all employer contributions. If you’re not maximizing your employer match, make that your first priority—it’s an immediate 50% or 100% return on your money, which you’ll never get anywhere else. Only after you’re capturing the full match should you consider other savings vehicles.

Mistake 3: Treating Savings Rate as a Static Number

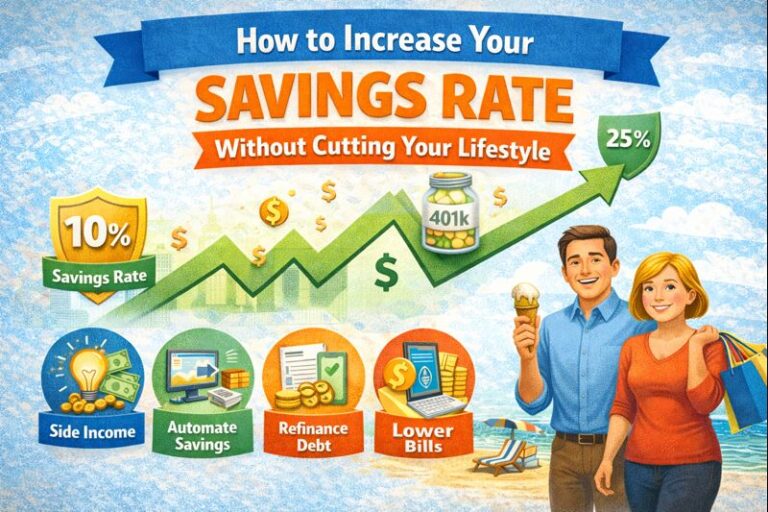

Many people set a savings rate once—maybe they decide to save 10% after reading a personal finance article—and then never revisit that number again. Meanwhile, years pass, their income increases, their life circumstances change, but that 10% savings rate remains unchanged. This is a massive missed opportunity that keeps people stuck far longer than necessary.

Your savings rate should be dynamic, evolving with your income and life stage. When you get a raise, promotion, or bonus, that’s the perfect time to increase your savings rate. The key is to do this before lifestyle inflation kicks in. If you get a 5% raise, immediately increase your savings rate by 2-3%. You’ll still enjoy some benefit from the raise in your take-home pay, but you’re also accelerating your wealth building.

This concept—sometimes called “save the raise”—is incredibly powerful because it allows you to increase your savings rate without feeling any decrease in your current lifestyle. You were already living comfortably on your previous income, so directing part of the increase to savings doesn’t require sacrifice. It just prevents lifestyle inflation from consuming every penny of your income growth.

The same principle applies when major expenses end. When you pay off your car loan, that monthly payment shouldn’t just disappear into general spending—it should redirect to savings. When your childcare costs end because the kids start school, increase your savings rate. When you pay off student loans, convert that payment into retirement contributions. Every financial milestone that frees up cash flow is an opportunity to boost your savings rate.

The Savings Rate Escalator

Create what I call a “savings rate escalator”—a plan for systematically increasing your rate over time. Start wherever you are now, even if it’s just 5%, then commit to increasing by 1% every six months or by 2-3% with every raise. This gradual escalation feels painless because you’re never making dramatic cuts to your current spending, but over five years, it can take you from a 5% savings rate to 20% or higher.

Set calendar reminders to review your savings rate quarterly. Ask yourself: Has my income changed? Have any major expenses ended? Am I still on track for my goals? This regular review ensures your savings rate evolves with your circumstances rather than remaining frozen at whatever arbitrary number you chose years ago.

Mistake 4: Not Defining What Counts as Savings

This might sound like a technical detail, but confusion about what actually counts toward your savings rate causes many people to either overestimate their progress or miss opportunities to increase it. I’ve met people who counted paying down their mortgage principal as “savings” while others didn’t count their 401(k) because they couldn’t access it. This inconsistency makes it impossible to accurately track progress or compare your performance to benchmarks.

Here’s a clear framework: Your savings rate should include all money that increases your net worth and isn’t immediately consumed. This includes retirement account contributions (401k, IRA, etc.), employer matching contributions, transfers to savings accounts, contributions to investment accounts, HSA contributions, and 529 education savings. All of these build your wealth and should count.

What shouldn’t count? Minimum debt payments generally don’t count as savings—you’re just paying what you owe. However, there’s a reasonable case for counting extra principal payments on mortgage or student loans since these do increase your net worth. The key is consistency: choose a definition and stick with it so you can accurately track your progress over time.

The confusion often arises with different types of accounts. Some people think, “I can’t touch my 401(k) for decades, so it doesn’t really feel like savings.” But that’s exactly what makes it powerful savings—it’s money you’re keeping for future you rather than spending on present you. That’s the definition of savings, even if it’s locked up for the long term.

Get crystal clear on your definition, then calculate your actual savings rate using that definition. Many people are pleasantly surprised to discover they’re saving more than they thought, while others realize they need to be more aggressive. Either way, clarity removes the confusion that keeps people stuck.

Mistake 5: Ignoring the Power of Small Percentage Increases

There’s a psychological tendency to think that small changes don’t matter. If you’re currently saving 8% of your income, increasing to 9% feels trivial—it’s just one percentage point. So people don’t bother with these small increases, waiting instead for some magical moment when they can make a dramatic change from 8% to 20%. That moment rarely comes.

The math tells a different story. Small, consistent increases compound into dramatic results over time. Let’s say you earn $60,000 annually. A one percentage point increase in your savings rate means an additional $600 saved per year, or $50 per month. Over 30 years, assuming 7% annual returns, that single percentage point difference adds approximately $56,000 to your retirement savings. And that’s just one point.

If you increase your savings rate by just 1% annually for five years—going from 8% to 13%—you’ve added five percentage points that will compound over your career. On a $60,000 salary, that’s an extra $3,000 per year, which over 25 years at 7% returns becomes roughly $190,000. These “trivial” increases are anything but trivial when you run the numbers.

The beauty of small increases is that they’re psychologically manageable. Increasing your 401(k) contribution from 8% to 9% probably means $40-50 less in your monthly paycheck. You likely won’t even notice that decrease. But you will definitely notice the long-term impact on your wealth.

The One Percent Strategy

Implement what I call the “one percent strategy”: Every six months, increase your savings rate by 1%. Set a recurring calendar reminder. When it pops up, log into your 401(k) and bump up your contribution percentage by one point. Do this consistently for three years, and you’ve added six percentage points to your savings rate—the difference between mediocre and excellent savings behavior.

The key is making the increases small enough that they don’t trigger lifestyle changes or require significant sacrifice. You’re essentially harnessing the power of marginal gains—small improvements that compound into major results over time.

Mistake 6: Lifestyle Inflation Consuming Income Growth

Here’s a pattern I see constantly: Someone starts their career earning $45,000 and saving $300 monthly (8% savings rate). Five years later, they’re earning $65,000—a 44% income increase. Yet they’re still only saving $300 monthly, which is now just 5.5% of their income. Their savings rate actually decreased as their income grew because lifestyle inflation consumed 100% of their raises.

Lifestyle inflation is the silent killer of financial progress. It’s the upgrade from a studio apartment to a one-bedroom, then to a two-bedroom. It’s the newer car, the nicer restaurants, the better vacations. None of these upgrades are wrong individually, but when every single dollar of income growth immediately flows to lifestyle expenses, your savings rate stagnates or even declines while you feel like you’re working harder than ever.

The insidious part is that lifestyle inflation feels justified. You’re earning more, so you deserve nicer things, right? The problem isn’t treating yourself occasionally—it’s allowing your entire standard of living to rise in lockstep with every raise. This keeps your savings rate frozen while your income climbs, meaning you’re not actually improving your financial position despite career advancement.

The antidote is to split income increases between lifestyle and savings. When you get a raise, commit to directing at least 50% of the after-tax increase to savings. If your raise gives you an extra $200 monthly in take-home pay, increase your savings by $100 and enjoy the other $100. This way you still benefit from your hard work and career growth, but you’re also accelerating your path to financial security.

Some people take this even further with the 80/20 rule: save 80% of raises and spend 20%. This aggressive approach rapidly increases your savings rate while still allowing some lifestyle improvement. The key insight is that you were already living comfortably before the raise. The additional income is a bonus, not a requirement for happiness.

Mistake 7: Not Having Different Savings Buckets for Different Goals

Many people make the mistake of lumping all their savings into one category without distinguishing between different purposes and time horizons. They have a vague notion of “saving money” but no clear structure. This creates several problems that keep people stuck in the paycheck-to-paycheck cycle.

First, when all your savings sit in one undifferentiated pile, it’s too easy to raid it for non-emergencies. Your “emergency fund” becomes a “whatever fund”—home repairs, vacations, holiday gifts all come from the same place. Then when a real emergency hits, there’s nothing left because you’ve been slowly depleting it for months.

Second, without separate buckets, you can’t optimize your money for different time horizons. Money you need in six months for a down payment shouldn’t be invested in the stock market, but money you won’t need for 30 years absolutely should be. When it’s all mixed together, you either take too much risk with short-term money or too little risk with long-term money.

Third, seeing progress toward specific goals is psychologically powerful. Watching your “house down payment fund” grow from $5,000 to $20,000 provides motivation and momentum. A generic savings account balance that fluctuates up and down provides neither.

Create distinct buckets: an emergency fund in a high-yield savings account, retirement savings in tax-advantaged accounts, short-term savings for planned expenses within 1-3 years, and long-term investment accounts for goals beyond three years. Each bucket serves a specific purpose and has appropriate investment vehicles.

Your savings rate should fund all these buckets appropriately. If your target is 20% savings rate, you might allocate 12% to retirement accounts, 5% to emergency fund building until it’s fully funded, and 3% to short-term savings goals. This structure ensures you’re making progress on multiple fronts simultaneously rather than robbing Peter to pay Paul.

Mistake 8: Waiting for Perfect Conditions to Start Saving

This might be the most destructive mistake of all because it delays everything indefinitely. People tell themselves: “I’ll start saving seriously once I pay off my student loans,” or “I’ll save more when I get my next raise,” or “I’ll focus on savings after the holidays.” Meanwhile, months turn into years, conditions never become perfect, and savings never happens.

The waiting trap is particularly common around debt. People think they must be completely debt-free before they can save, so they throw every extra dollar at loans while contributing nothing to retirement accounts. This sounds logical but ignores two crucial factors: time and opportunity cost.

First, compound interest requires time to work. Every year you delay saving is a year of growth you can never recapture. Starting at 25 versus 35 with the same savings rate can mean a difference of hundreds of thousands of dollars at retirement. Waiting for perfect conditions robs you of your most valuable asset—time.

Second, some debts have low enough interest rates that you’re better off saving while making minimum payments. If you have a 3% student loan and your employer offers a 401(k) match, you’re objectively better off capturing that match (a 50-100% instant return) than paying extra on the 3% loan. Perfect shouldn’t be the enemy of good.

The right approach is to start saving something—even 5% or 8%—while simultaneously working on other financial goals. Yes, you should pay down high-interest debt. Yes, you should build an emergency fund. But you should also be contributing to retirement accounts, especially if there’s an employer match. These goals aren’t mutually exclusive; they’re complementary.

The Minimum Viable Savings Rate

Implement what I call the “minimum viable savings rate”—the smallest amount you can save right now given your circumstances. Maybe that’s only 5% or 6% because you’re aggressively paying off credit cards. That’s fine. Save the 5%, capture your employer match, and commit to increasing once the cards are paid off.

The act of saving something—anything—is psychologically powerful. It establishes the habit, creates momentum, and proves to yourself that you can do this. Starting with 5% and increasing is infinitely better than waiting for perfect conditions to save 20%, because those perfect conditions rarely arrive.

Breaking Free from the Paycheck-to-Paycheck Cycle

These mistakes are interconnected, and most people stuck in the paycheck-to-paycheck cycle are making several of them simultaneously. You’re saving whatever’s left (nothing), not capturing your full employer match, treating your savings rate as static, letting lifestyle inflation consume raises, and waiting for perfect conditions that never arrive. It’s not surprising you feel stuck—you’re fighting against yourself with flawed systems.

The good news is that fixing these mistakes creates dramatic results surprisingly quickly. Here’s what breaking free looks like:

Start by automating a pay-yourself-first savings rate of at least 10%, including your full employer match. That’s your baseline, your non-negotiable foundation. Even if it feels impossible at first, force yourself to make it work by adjusting spending. The discomfort will fade within weeks as you adapt.

Create a savings rate escalator—plan to increase by 1% every six months or by half of every raise. Set calendar reminders so this happens automatically without requiring ongoing motivation.

Establish separate savings buckets with clear purposes. Set up automatic transfers to each: retirement accounts, emergency fund, short-term savings. Watch each bucket grow and feel the psychological win of progress toward multiple goals.

Reject lifestyle inflation as a default setting. When your income increases, consciously decide how to allocate it rather than letting it disappear into vaguely nicer living. Some can go to lifestyle—you should enjoy your success—but not all of it.

Finally, abandon the waiting trap. Your conditions will never be perfect. Start saving now at whatever rate you can manage, then increase it as circumstances improve. Action beats perfection every single time.

Most people living paycheck to paycheck aren’t there because they don’t earn enough—they’re there because of systemic mistakes in their savings approach. Fix the system, and the results change almost immediately. Within three to six months of implementing these corrections, most people report feeling noticeably less financial stress. Within a year, they have emergency funds that would have seemed impossible before. Within five years, they’re on track for retirement goals that once felt like distant fantasies.

The paycheck-to-paycheck cycle isn’t a permanent condition—it’s a pattern created by specific mistakes. Identify which mistakes you’re making, correct them systematically, and watch how quickly your financial reality transforms. The life you want isn’t about earning more money. It’s about keeping more of what you earn, and that starts with avoiding these common savings rate mistakes that keep too many hardworking people stuck.